In the words of David Treleaven, an educator and psychotherapist whose work focuses on the intersection of trauma and mindfulness “placed beside one another, mindfulness and trauma can seem like natural, even inevitable, allies. While trauma creates stress, mindfulness has been shown to reduce it.”

Given this, the assumption that anyone experiencing traumatic stress would automatically benefit from practising mindfulness is understandable. The relationship between mindfulness and traumatic stress, however, is not quite so straightforward.

On the one hand, mindfulness can be an extremely valuable resource for people experiencing traumatic stress. Mindfulness enhances awareness of the present moment, strengthens the ability to self-regulate and increases self-compassion, each of which are important skills for trauma recovery. However, mindfulness can also exacerbate the symptoms of traumatic stress as paying close, sustained attention to one’s inner world can mean coming into contact with trauma related stimuli in the body (e.g. flashbacks, heightened emotional arousal) potentially leading to feelings overwhelm and dysregulation.

![]()

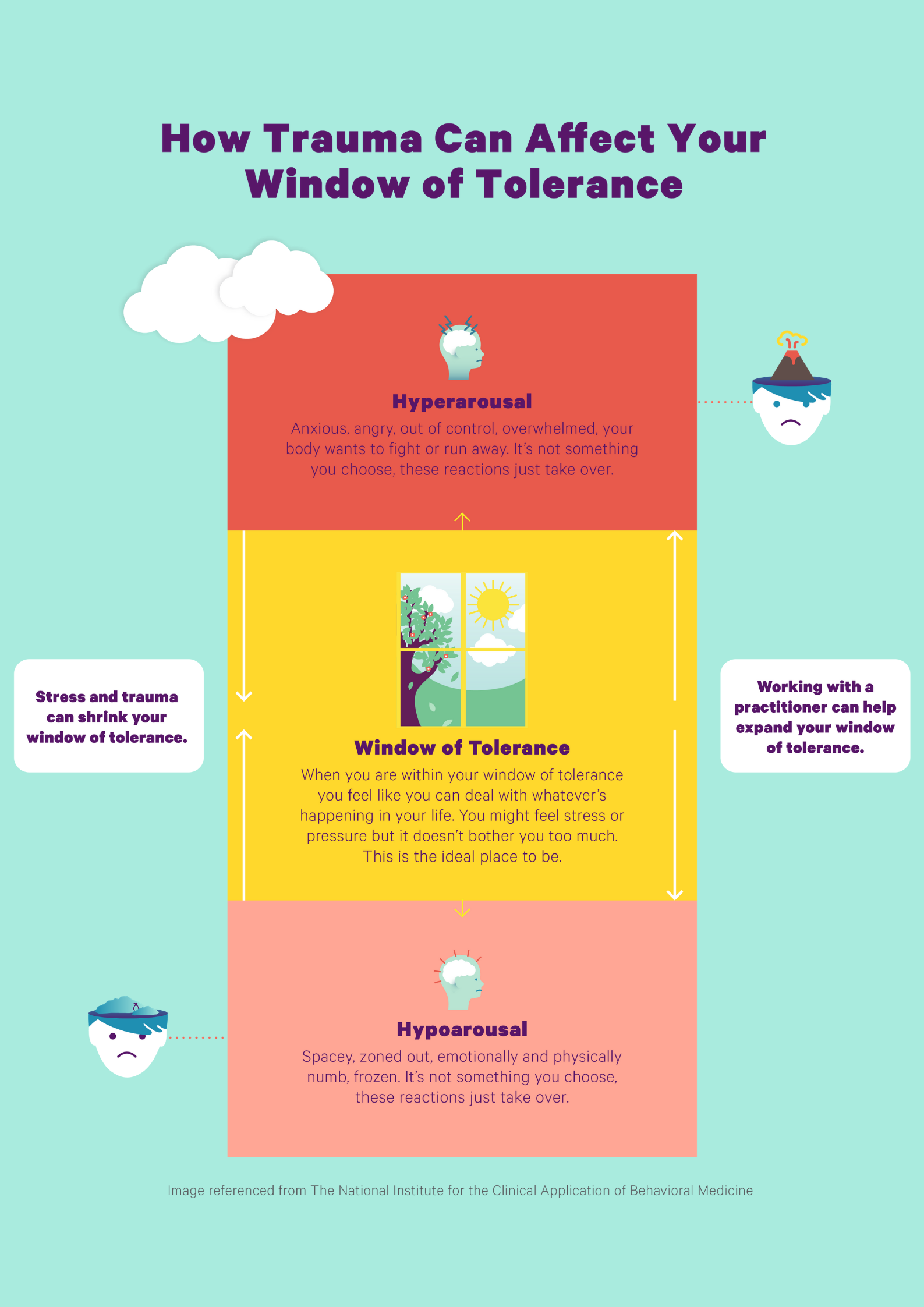

Given that mindfulness can be an invaluable aspect of trauma recovery, how then can the potential pitfalls of mindfulness be minimised and the benefits of mindfulness maximised? Having tools inside your mindfulness practice that you can use if you start to feel overwhelmed or dysregulated is one of the ways we can do this - tools to support you to return to your ‘Window of Tolerance’.

The ‘Window of Tolerance’ is a concept, coined by Dr. Daniel Siegel, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA, which proposes that we all have an optimal level of physiological arousal level. When we’re inside our ‘Window of Tolerance’ we’re somewhat stable and regulated and able to handle the waves of stress that will inevitably happen in our day, it is our optimal zone of physiological arousal.

When we’re outside of our ‘Window of Tolerance’ there is either too much or too little physiological arousal in our system . We’re either hyper (i.e. over) aroused (e.g. highly anxious, hypervigilant, overwhelmed, stressed) or hypo (i.e. under) aroused (e.g. we’re feeling numb, spacey, dissociated, deeply disorganised). People who have experienced trauma often experience something known as ‘dysregulated arousal’, which is uncontrollably cycling back and forth between hyper and hypo-arousal and their ‘Window of Tolerance’ becomes narrower. These are some of the most painful aspects of traumatic stress.

Some of the tools that you can use to support you inside your mindfulness practice are outlined in the ‘Best Practice Guidelines’ below.

Best Practice Guidelines for your Mindfulness Practice:

Know that more isn’t always better

We recommend starting with shorter mindfulness practices and build up slowly. You could start with short 2-3 minute grounding practices such as ‘Counting & Blowing’, ‘Three Things’ or ‘Roots to the Ground’ which you’ll find in the Stress Management Program in the Smiling Mind App.

Remember that you are always in choice

It is important to know that you are always in choice during your mindfulness practice. At any time during a mindfulness practice you can:

- Take a break if you need to and come back when you’re ready (or not if it doesn’t feel right);

- If you need to you could take a break by opening your eyes, stretching, offering yourself a form of soothing touch (e.g. placing a hand over your heart or holding one hand in the other);

- Practise with your eyes open or closed;

- Open your eyes (if they’re closed) at any time;

- Shift your posture at any time to feel more grounded and safe;

- Meditate seated, standing or lying down in whatever position feels most comfortable.

Know that the breath isn’t always a neutral anchor of attention

Using the breath as an anchor of attention is a very common starting place for mindfulness meditation instruction as it’s so accessible and is often assumed to be neutral. However, this is not necessarily the case.

For people impacted by trauma paying attention to the breath can sometimes lead to feeling dysregulated.

Why is this? Our respiratory system is closely connected to our sympathetic nervous system which is tied to traumatic stress. The sympathetic nervous system is sometimes referred to as our body’s accelerator. When we face a significant amount of threat the accelerator slams to the floor, automatically stimulating the ‘fight or flight’ response taking us out of our ‘Window of Tolerance’.

When people are experiencing ongoing symptoms of traumatic stress it’s like the accelerator remains slammed to the floor which can create a lot of pain and complications in the body. The body holds reminders of a trauma in the form of bodily sensations. Paying close, sustained attention to the breath may, therefore, bring you into contact with traumatic stimuli.

Experiment to find a neutral anchor of attention that works for you

It’s important to know that there are different anchors of attention that you can use in your mindfulness practice. No one anchor of attention is better than another - the underlying principles of mindfulness meditation are the same.

We encourage you to experiment with different types of meditation to find one (or more) anchor(s) that is comfortable for you to work with. ![]()

Examples of different anchors of attention:

- Sounds in the environment (e.g. ticking clock, hum of an appliance, wind, birdsong, music);

- Body (e.g. a neutral sensation in part of your body such as your feet touching the ground, hands in your lap; the whole body);

- Image/object (e.g. flower, candle flame, photograph)

- Movement (e.g. walking meditation, mindful movement practice such as yoga, qigong)

- Object (e.g. holding a tactile object such as a smooth stone)

mantra (e.g. a sound, word or short phrase)

![]()

Keep checking in with yourself & assessing how mindfulness is affecting you

It’s important to keep in mind that experiencing traumatic stress doesn't necessarily mean you will have a negative experience with mindfulness. Many people who have experienced trauma have an extremely positive experience with mindfulness. It is, however, important to keep checking in with yourself and assessing how your meditation practice is actually affecting you. Ask yourself:

- How is meditation affecting my mood?

- How is meditation affecting my well-being?

- How is meditation affecting my ability to stay regulated?

- Do I feel more or less regulated after meditation?

It’s important to be honest with yourself. Mindfulness won’t work well for everyone so it’s better not to force it.

![]()

And finally...

It is important to be aware that while mindfulness can be an extremely valuable resource for anyone experiencing traumatic stress, mindfulness alone is not enough in and of itself for trauma recovery. Other tools and resources are also required. If you are, or think you might be, experiencing traumatic stress we recommend speaking with your GP to find a psychologist who specialises in trauma.

How do you know if this is happening? You might have had or begin to experience symptoms associated with stress or trauma - feelings of shock, denial, disbelief, confusion, difficulty concentrating, anger, irritability, mood swings, anxiety, guilt, shame, self-blame, withdrawing from others, feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, disconnected, numb, difficulty sleeping or nightmares, memories, overly tired, easily startled, racing heartbeat.

Trauma focused psychotherapies include (but are not limited to) trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy (TF-CBT); eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR); internal family systems therapy (IFS); Sensorimotor Psychotherapy.

![]()

Recommended Resources

Books

- Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness: Practices for Safe and Transformative Healing by David A. Treleaven

- The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel A. van der Kolk

- Healing Trauma by Peter Levine

- The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment by Babette Rothschild

- Widen the Window: Training Your Brain and Body to Thrive During Stress and Recover from Trauma' by Elizabeth Stanley

.jpg)

.jpg)